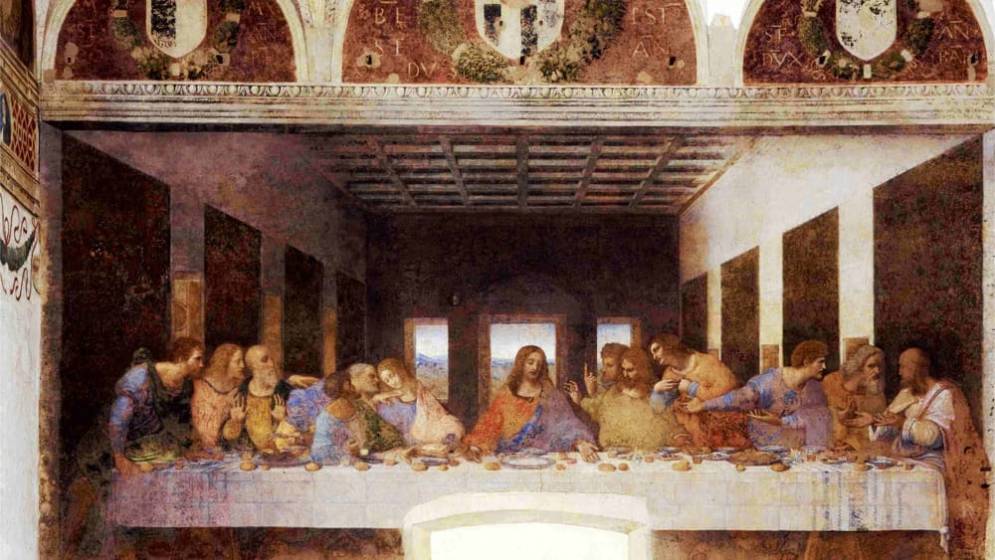

Cenacolo Vinciano, the “Last Supper” signed by Leonardo da Vinci

One of the world’s most renowned artworks, the Cenacolo Vinciano, commonly known as the “Last Supper,” was crafted by the genius Leonardo da Vinci in the refectory of the adjoining convent to Santa Maria delle Grazie between 1494 and 1497.

This convent, linked to the Sforza Castle through an underground passage, underwent a transformation in 1490 when Ludovico Sforza chose to convert the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie into his personal mausoleum. He entrusted the esteemed architect Donato Bramante with the construction of an exquisite dome, a charming small cloister, and a sacristy, adorning them with frescoes by prominent artists from the Lombardy school. Leonardo’s “Last Supper” is a significant part of this collection of exceptional artworks.

Da Vinci’s masterpiece graces one wall of the vast refectory, opposite the grand scene of the “Crucifixion” by Donato Montorfano, where faint profiles of various members of the Duke’s family can be discerned.

The creation of the “Last Supper” commenced around 1494 and concluded in 1497. Leonardo painstakingly attended to every aspect of his work, beginning with the overall concept of the wall, including the lunettes at the top featuring the Sforza coats of arms and garlands of fruit and flowers, along with the depiction of the Last Supper. His attention then turned to the general composition and individual figures. His work pace was unpredictable; he might go days without touching a paintbrush or spend hours on the scaffolding.

For this masterpiece, da Vinci departed from the conventional fresco technique, which requires swift application of paint on a thin layer of wet plaster before it dries. Instead, he sought a method that allowed for continual adjustments. Unfortunately, a few years after the fresco’s completion, the paint began to detach from the plaster, and the supporting layer gradually deteriorated.

Subsequently, the artwork endured more severe damage, including misguided attempts to remove it from the wall, disastrous restoration efforts, and the installation of a door, later bricked up, at the center of the wall beneath the figure of Christ. During Napoleon’s reign, the refectory was repurposed as a stable, and during wartime bombing raids in 1943, both the side walls and the roof collapsed.

Over two decades of painstaking restoration work ensued, removing accumulated dirt and previous interventions, revealing significant portions of the original painting, though fragmented into small pieces. Dust remains a major culprit in its deterioration, necessitating constant monitoring of the refectory and visitor traffic.

Leonardo da Vinci, a luminary of the Italian Renaissance and a forerunner of modern thought, was born in Tuscany and passed away in France in 1519, marking five centuries since his death. While he resided in Florence, Rome, and Venice in Italy, Milan held a special place in his heart, where he spent over two decades, initially at the court of the Sforza and later during French rule. Leonardo saw painting and drawing as means to explore and understand the world.

Arriving in Milan at the age of thirty, Leonardo presented himself to Ludovico Sforza, Il Moro, with a letter showcasing his remarkable talents as an inventor and artist. Lombardy offered him a vibrant, intellectually stimulating environment with access to advanced books and resources, ideal for nurturing his status as a “universal man.” Milan warmly embraced Leonardo, recognizing his genius and supporting his work.

Five centuries later, we can still trace the footsteps of this Tuscan genius, whose presence is woven into Milan’s art and culture. In addition to the “Last Supper,” one of the world’s most famous paintings, found in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan houses other works and memories of Leonardo.

At the Sforza Castle, you can admire various drawings, the “Codex Trivulzianus,” and the frescoed “Sala delle Asse” by da Vinci. The Ambrosiana Art Gallery and Library display the “Portrait of a Musician,” the only oil-on-wood painting by Leonardo remaining in Milan, along with an extensive collection of drawings and writings in the “Codex Atlanticus.”

Furthermore, Milan’s science museum, the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia, showcases models and reproductions of his inventions. Various museums in the city exhibit works by artists inspired by Leonardo. Near the San Siro Racecourse, visitors can marvel at a colossal bronze horse statue, an equestrian monument based on the artist’s drawings.

The cloisters of Ca’ Granda-Ospedale Maggiore still carry the legacy of Leonardo’s anatomy studies, while his contributions to hydraulic engineering come to life in the Darsena and Navigli area. Finally, next to Santa Maria delle Grazie, you can visit La Vigna di Leonardo, the vineyard gifted to him by Ludovico Sforza, a testament to their enduring connection.